OVERVIEW

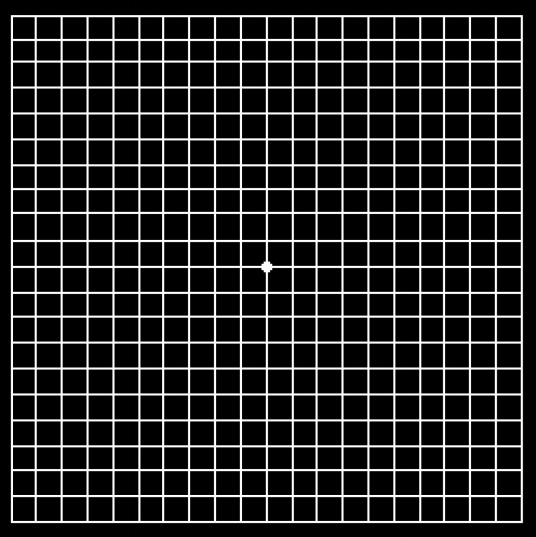

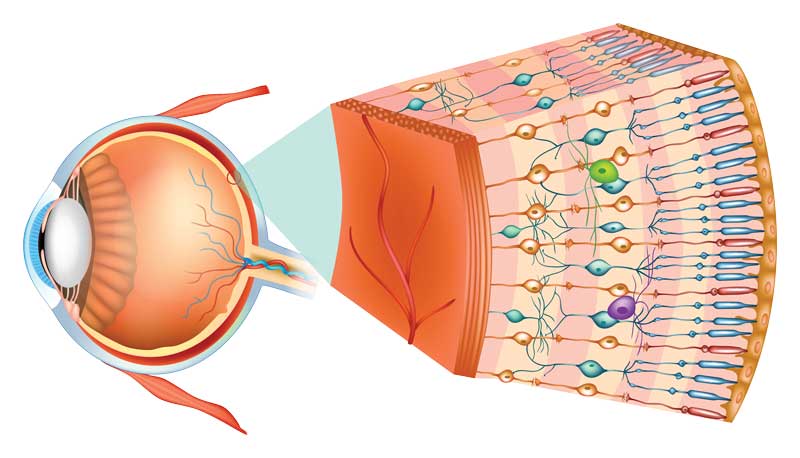

Age Related Macular Degeneration (AMD) is a deterioration or breakdown of the macula (center of the retina) and is one of the most common causes of poor vision in people over age 60. The visual symptoms of AMD involve the loss of central vision (reading, recognizing faces, etc.), while peripheral vision is unaffected. While age is the most significant risk factor for developing AMD, heredity, blue eyes, high blood pressure, cardiovascular disease, and smoking have also been identified as risk factors.

While AMD is one disease, it may be categorized into two forms: wet and dry. Both are explained in more detail below.